This is the fourth in a series of articles to illustrate how to critically think and reflect upon practice problems. Be sure to read the first three articles in the series:

The previous article in this series focused on evaluating information to make clinical decisions when caring for your patients. Recall that our pharmacist applied her critical appraisal skills to evaluate evidence she found through a PubMed Clinical Queries search. She applied these skills to determine the appropriateness of the prescription for mirabegron for her pediatric patient. After assessing the evidence, the pharmacist had a few concerns:

- The study sample size was relatively small (only 14 girls were enrolled).

- The study had no placebo control group.

- There were no summary resources and only a limited number of other single studies available to review.

She determined that the evidence on its own was not enough to make a clinical decision. The pharmacist decided that her next step should be to discuss her findings with the patient’s father and with the prescribing physician. Although she has critically appraised the best available evidence, this is only one component of practising evidence-based medicine (EBM), or in this case, evidence-based pharmacy.

Evidence-based medicine[1]

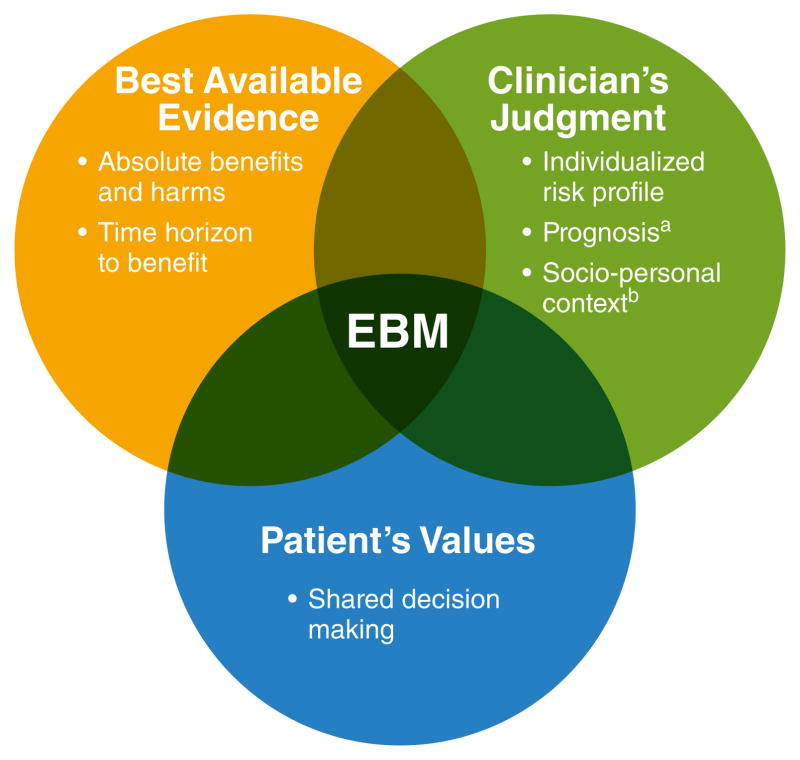

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) has been defined as the integration of best available evidence, clinical expertise, and patient values into the decision-making process when caring for patients.[2]

The evidence is used as a tool to inform your judgment and the patient’s choice.

Keep in mind that the “best available” evidence may not necessarily be good evidence. You may need to do your best in working with evidence that is weak, incomplete, and/or conflicting. However, the evidence is just one component of EBM. All three components are essential when making informed clinical decisions. Determining the patient’s needs with her father is vital for providing person and family-centred care. Collaborating with the physician is important in considering the prescriber’s judgment as well as her own.

For an explanation of the intersection of these three elements of EBM, watch the four-minute video found on the University of Toronto Libraries website.[3]

Discussion with the patient’s father

Pharmacist: Thank you for giving me time to do some research for this new prescription. I just want to make sure your daughter gets the right medication, so she doesn’t keep wetting herself during the day. I understand that this has been really upsetting for her. This particular drug hasn’t been used very often in young girls and I found limited information to show it will be safe and effective for children.

Patient’s father: Ok, well what do you recommend? I don’t feel comfortable with my daughter using something that isn’t proven to work.

Pharmacist: I’d like to discuss some other options with your daughter’s doctor. One option, called tolterodine, is very similar to the medication that your daughter tried in the past and the side effects may be more tolerable. I’d like to suggest a trial of this medication before we consider drugs like mirabegron.

Patient’s father: Yes, thank you, I’d prefer that approach. Please chat with her doctor. I’d appreciate if you could call me at home when you hear back.

The receptionist at the medical clinic says the physician is with another patient and asks the pharmacist to fax her question.

October 9, 2020

PRESCRIPTION CLARIFICATION for Jane Doe

Hello Dr. Smith,

I was hoping to discuss your recent prescription for mirabegron for Jane’s overactive bladder (OAB). I confirmed with her father that she has continued to experience urgency with frequent loss of urinary control. Her Netcare profile indicates previous use of oxybutynin; her father said Jane didn’t tolerate it due to anticholinergic side effects such as constipation. I reviewed current non-pharmacologic treatments the family is using (e.g., scheduled voiding).

I reviewed the evidence for the use of mirabegron in pediatric patients for OAB. The most relevant evidence I found had limited data for pediatric female patients (n=14) and no placebo control group.* I could not find any summary resources and only limited relevant single studies were available to review.

Although Jane has previously tried oxybutinin, she has never had a trial of tolterodine. After speaking with her father about some of the limitations of the available evidence, he decided he might feel more comfortable trying tolterodine for Jane first. As per the treatment algorithm in RxTx for urinary incontinence in children, tolterodine may be considered as an alternative for urge symptoms. When I’ve researched this in the past, I reviewed some summary evidence showing that tolterodine has similar efficacy and improved tolerability over oxybutynin.**

Would you consider modifying the prescription to tolterodine 2-4mg po qHS x 1 month?

I’d be happy to discuss the matter further by phone so I can better understand your perspective. If you know of other evidence that I haven’t considered, I’d appreciate if you could share this with me.

Sincerely,

Mary Miller

Pharmacist

MM Apothecary

* Blais AS, Nadeau G, Moore K, Genois L, Bolduc S. Prospective Pilot Study of Mirabegron in Pediatric Patients with Overactive Bladder. Eur Urol. 2016;70(1):9-13.

**Medhi B, Mittal N, Bansal D, Prakash A, Sarangi SC, Nirthi B. Comparison of tolterodine with standard treatment in pediatric patients with non-neurogenic dysfunctional voiding/over active bladder: a systematic review. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013 Oct-Dec;57(4):343-53.

How would you communicate your findings to the patient’s father and the prescriber? Do you agree with our pharmacist? Compare your answers with a colleague.

To summarize, practising evidence-based pharmacy has several interdependent components:

- critically appraising (or finding and evaluating) best available evidence;

- determining patient needs and goals as part of person and family-centred care; and

- collaborating with other health professionals in applying clinician judgment.

Since the well-being of our patients is at the centre of everything we do as pharmacy professionals, incorporating evidence-based pharmacy into daily practice will help us care for our patients and meet standards.

[1] Makam AN, Nguyen OK. An Evidence-Based Medicine Approach to Antihyperglycemic Therapy in Diabetes Mellitus to Overcome Overtreatment. Circulation. 2017 Jan 10;135(2):180-195.

[2] Sackett D, Strauss S, Richardson W, et al. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2nd ed. Churchill Livingstone; Edinburgh: 2000

[3] https://guides.library.utoronto.ca/evidencebasedmedicine. Accessed September 30, 2020.